The 125th anniversary of the Wilmington NC coup is upon us. To mark the anniversary, I recommend reading Wilmington’s Lie: The Murderous Coup of 1898 and the Rise of White Supremacy by David Zucchino.

I’m embarrassed to admit that despite living in North Carolina for nearly 3 decades, I didn’t know the details of this event. If you’re like me and been mostly oblivious, let me fill you in.

In the post-Reconstruction South of 1898, Wilmington was a majority black town filled with successful black merchants, bankers, police officers, magistrates, and postal workers. Blacks held a few seats on the local Board of Aldermen. One black man served in the US House of Representatives.

Whites viewed this as a problem. Zucchino describes the thinking in his Pulitzer Prize winning book. “For whites in Wilmington, blacks had ceased to be slaves, but they had not ceased to be black. They were still considered unworthy, unequal, and inferior, still subservient to whites by any measure.”

The plan for violence had been building for months. Josephus Daniels, publisher of Raleigh’s News and Observer, led a propaganda campaign to convince whites of the danger of blacks as voters and blacks as citizens. Red Shirts (a group as bad as or worse than the KKK) roamed black neighborhoods firing guns and beating men to terrorize them out of voting on November 8. On Election Day, white supremacists blocked roads and stuffed ballot boxes, sometimes with more votes than voters in the precinct.

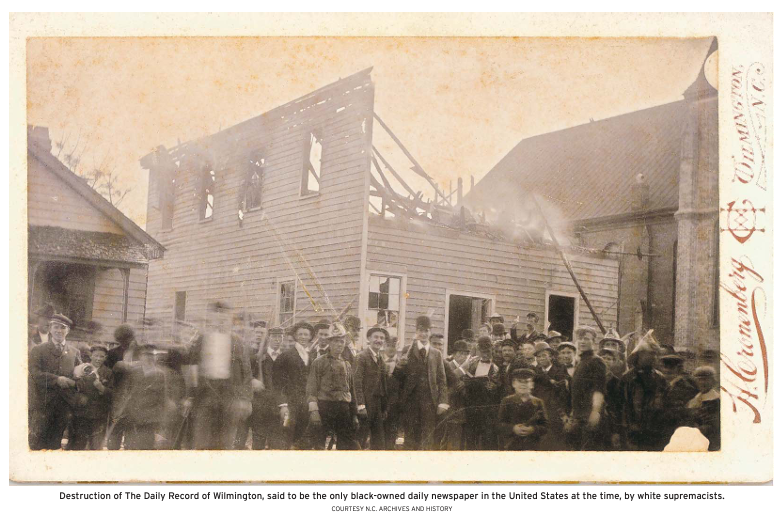

November 10 was the final wave of the campaign, the final drive to get blacks out of Wilmington leadership and Wilmington livelihood. On that day, a mob of white men roved the streets on horseback and on foot. In addition to the weapons they had accumulated for months, they were accompanied by military units and two machine guns. The mob torched the home of the Daily Record, a black-owned newspaper. They terrorized families out of their homes and into the neighboring swamp. They forced black officials and their white allies to resign, then physically removed them from town. They shot men in the street. At the end of the day, somewhere between 9 and 300 blacks were dead.

The coup succeeded. Afterwards the new white supremacist government enacted the grandfather rule, which by law restricted voting to only those whose grandfathers had voted. In 6 years the number of registered black voters in NC dropped from 126,000 to 6,000. Jim Crow laws were established. It was nearly a century until the next black North Carolinian would be elected to the US House.

In the decades following, the perpetrators, who were never charged, were free to define the story of what happened that day. The truth was covered up by lies and justifications, glossed over, or ignored entirely until the myth was set in stone. Zucchino writes, “From the moment the first black man fell dead, Wilmington’s white leadership portrayed the day’s events as a justified, spontaneous response to a black riot.” White rule, per one of the white rioters, was “an inherent and traditional right”.

I found Wilmington’s Lie a difficult and disturbing read. Difficult not in language or grammar, but in hearing of the events of that time. Difficult in absorbing that white supremacists weren’t afraid to admit they were. Difficult in reading the tactics used to put blacks in their place and to retain power. Difficult in hearing the blatant disregard for lives and livelihoods simply for the color of one’s skin.

North Carolina has only recently begun to acknowledge the truth of its past, despite this year being the coup’s 125th anniversary. It wasn’t until 2006 that the News and Observer, the “militant voice of White Supremacy”, published a 16 page special edition owning up to the paper’s role in leading the coup. Only in 2019 did Wilmington replace the incorrect historic market with an accurate one. Not until 2020 was the statue of Josephus Daniels removed.

The event paints a picture of the white privilege that benefitted certain families for generations and devastated certain others. Ketanji Brown Jackson wrote of that privilege in her recent dissent of overturning affirmative action:

Imagine two college applicants from North Carolina, John and James. Both trace their family’s North Carolina roots to the year of UNC’s founding in 1789. Both love their State and want great things for its people. Both want to honor their family’s legacy by attending the State’s flagship educational institution. John, however, would be the seventh generation to graduate from UNC. He is White. James would be the first; he is Black. Does the race of these applicants properly play a role in UNC’s holistic merits-based admissions process?

Ketanji Brown Jackson

For those pressed for time, reading the shorter N&O article could suffice. But reading one or the other is a must for all North Carolinians. For all Americans. Not because we should use it to blame or exonerate a political party. But instead to know what people are capable of. To know the lies that have been passed down in families. To know the hurt that lingers across the generations. To prevent it from happening again.

We are all free to disagree on policy. But we are not free to overthrow elected officials because they aren’t following our desired policy. I wonder what could have been if the allegiance between blacks and whites in Wilmington before the coup had been allowed to stand. Where, as a society, would we be today? Perhaps, I can naively hope, we might not be so divided. Perhaps, by reading this book, we can cure some of that division and move forward. Together.